-

Corvettes At Carlisle Celebrates 40 Years Of Fiberglass Fun by Carl Zander

Tuesday, Sep 27, 2022

It's been just over a month since Corvettes at Carlisle presented by eBay Motors set a NEW Fun Field record of 2,926 Corvettes. …Show More -

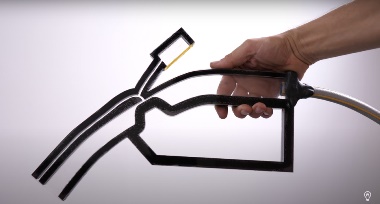

Learn the Fascinating Mechanics of How a Gas Pump Nozzle Knows When to Stop - By Erin Marquis

Tuesday, Sep 20, 2022

Have you ever put gas in your car with every intention of filling to the top, but the pump kicks off? From there, you're just topping it off, bu …Show More -

There's Something For Everyone At Carlisle Auction's All-Truck Hour by Johnny Puckett

Wednesday, Sep 14, 2022

Carlisle Auctions is back with the Fall Carlisle Collector Car Auction on September 29-30 at the Ca …Show More -

Truck Drivers Commitment to Delivering for American Communities Celebrated

Wednesday, Sep 7, 2022

Show MoreAnnually, the Carlisle Truck Nationals presented by A&A Auto Stores ho …

-

You NEVER Know What You'll See at Corvettes at Carlisle

Tuesday, Aug 30, 2022

Show MoreStaffers of Carlisle Events are privy to some things that we can't always share in advance of an event. Sometimes, w …

-

Dodge is Offering Some Cool Options as it Ends its Current Muscle Car Run in 2023 by Peter Valdes-Dapena

Wednesday, Aug 17, 2022

Big news coming out of Dodge the other day - so big in fact, it drew the attention of media from around the world. "The modern Dodge Challenger …Show More -

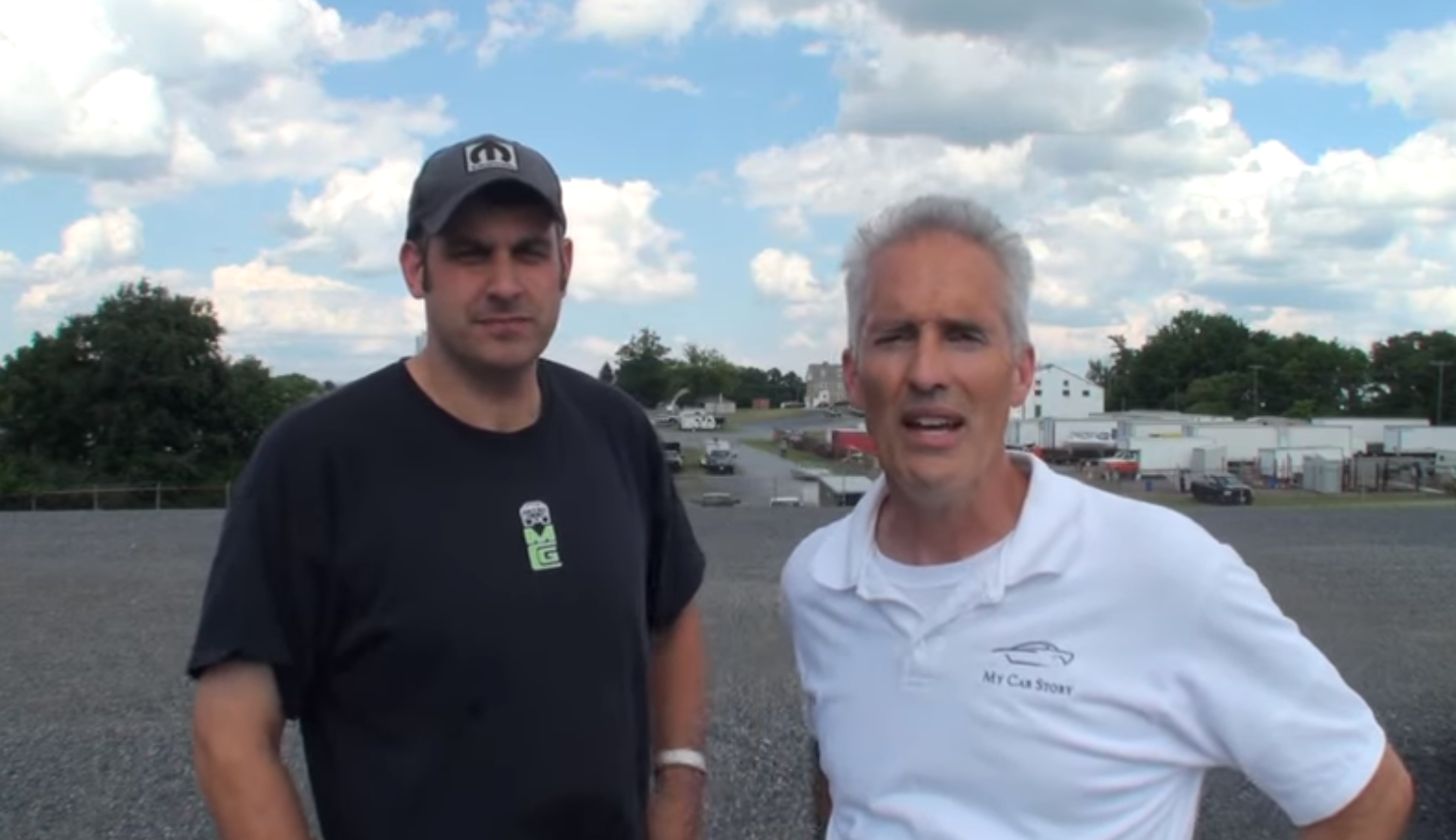

Hey Mom - Can I Borrow the Car? - Lou Costabile Returns with Another My Car Story

Thursday, Aug 11, 2022

As Dodge prepares for its Speed Week fun in Detroit, where they'll celebrate the brand and look forward to what's next, let's look back at this 1969 D …Show More -

Lou Costabile's Back with Another My Car Story - '58 Plymouth Belvedere

Thursday, Aug 4, 2022

While so many Mopar enthusiasts were walking the grounds at Carlisle July 15-17, 2022 to enjoy the annual Carlisle Chrysler Nationals car show, our fr …Show More -

My Car Story - Carlisle Chrysler Nationals Edition Part 2 by Lou Costabile

Thursday, Jul 28, 2022

This week on "My Car Story" Lou is showcasing another great ride and family as part of the 2022 Carlisle Chrysler Nationals. He's spotlighting a …Show More -

My Car Story - Carlisle Chrysler Nationals Edition by Lou Costabile

Wednesday, Jul 20, 2022

Car folks love to talk about their cars and fresh off a record-setting 2022 Carlisle Chrysler Nationals, our friend Lou Costabile has shared some …Show More -

Ready, Set, Cruise – 2022 Carlisle Chrysler Nationals is Here! - by David Hakim

Wednesday, Jul 13, 2022

It's Carlisle Chrysler Nationals weekend at the Carlisle PA Fairgrounds and renowned automotive writer David Hakim is back with a feature dedicated to …Show More -

Two Great Collections Planned for the Fall Carlisle Collector Car Auction

Thursday, Jul 7, 2022

A few times a year, the team from Carlisle Auctions is All About Cars...literally! This week's All About Cars blog post serves as a quick remind …Show More -

See What They're Saying Part 2 - Trucks of the Carlisle Ford Nationals

Thursday, Jun 30, 2022

Last month we shared a story for All About Cars that called out what industry writers were saying about the cars that adorned the National Parts Depot …Show More -

Back Home! - Checking out Bloomington Gold by Lance Miller

Wednesday, Jun 22, 2022

Show MoreJust like the titles reads, the 50th Anniversary Bloomington Gold Corvette event was held recently. The event has moved around frequentl …

-

See What They're Saying - News Stories from the Carlisle Ford Nationals 2022

Monday, Jun 13, 2022

Recently (June 3-5, 2022), Carlisle Events hosted its largest-ever car show; the Carlisle Ford Nationals presented by Meguiar's. …Show More -

How to Buy Your First Car - By Mike Garland

Wednesday, Jun 8, 2022

At some point, if we own a car, we bought one for the first time. Sometimes we were younger, other times we were older. Sometimes we did i …Show More -

Learning More About the Carlisle Chrysler Nationals - by Ed Buczeskie

Thursday, May 19, 2022

Every year our very own Ed Buczeskie pens (types) a piece for Mopar Collector's Guide. As the event manager for the Carlisle Chrysler Nationals, …Show More -

.tmb-thumb380.jpg?sfvrsn=13f1f5e3_0)

The Carlisle PA Fairgrounds - Historic, Family Friendly...Spacious

Thursday, May 12, 2022

Annually more than 500,000 guests trek to the Carlisle PA Fairgrounds for automotive events. The car shows at Carlisle as they are known by many …Show More -

These Are The Worst Cars Of The 1980s - by Owen Bellwood (Jalopnik)

Wednesday, May 11, 2022

There's a lot of great automotive content on the web. Some of that content is informative, some is entertaining. This piece we noticed on …Show More -

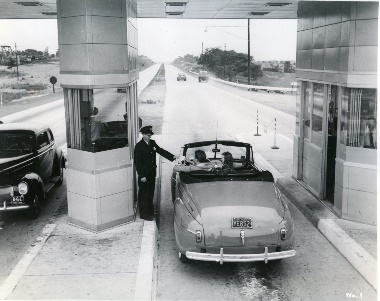

The History of the Pennsylvania Turnpike is...Historic - by Dan Cupper

Wednesday, May 4, 2022

Show MoreTo a historian, the Turnpike is one of the last great expressions of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and surely one of the most enduring. …

Book with a preferred Hotel

Book online or call (800) 216-1876